HISTORY 1990 -1991 Desert Shield/Desert Storm and the 1990s

1990

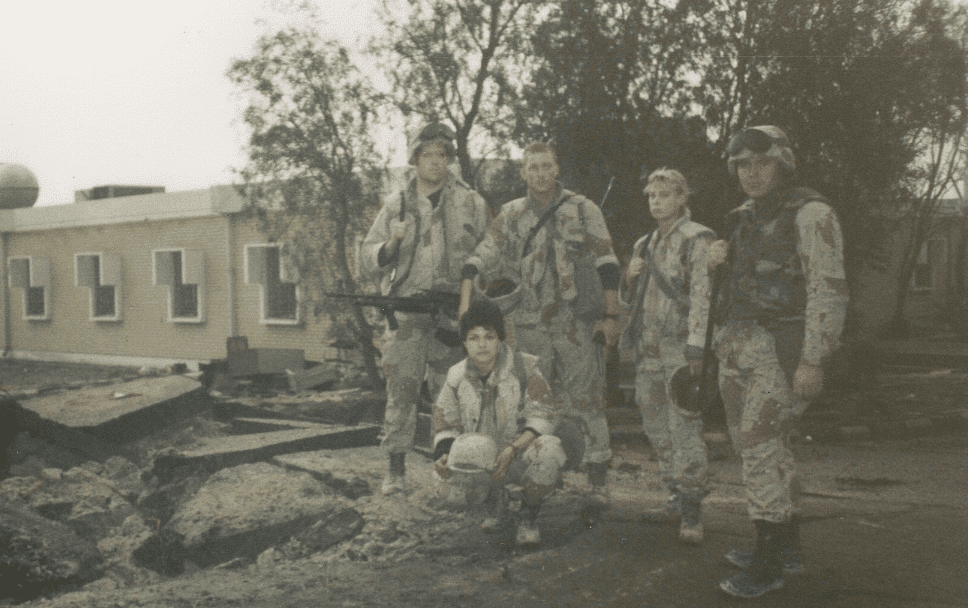

Persian Gulf during Operation Desert Storm

Sergeant Major Maria Connie Villiaescas deploys to Saudi Arabia.

Sergeant Major Maria C. Villescas joined the United States Marine Corps in 1982 at the age of 22. She wanted to get out of her native Los Angeles, the only place she’d ever lived. Her sister and uncle were both serving in the Marine Corps, and so she decided to follow in their footsteps.

Villescas entered boot camp in January of 1983. After completing boot camp, Villescas was assigned her Military Occupational Specialty (MOS): motor transport. At Camp Lejeune in Jacksonville, North Carolina, she trained as a motor vehicle operator of 18-wheeler trucks—a role which previously had only been filled by men.

At that time, 1983, women just didn’t drive combat trucks, because women weren’t allowed in combat. But we were the first group to get selected. And there was probably about eight females, and three of us passed.

Villescas spent her first four years driving tractor-trailers around Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, California. Eventually, she earned the begrudging respect of those to whom she referred as “old farts,” who initially questioned whether this petite 5’2” woman could drive such large vehicles. In her fifth year at Pendleton, she was given the opportunity to attend instructor school. She became the first female instructor to teach new Marines how to drive 16-wheeler vehicles—another milestone in her career.

Villescas arrived in Saudi Arabia in late October of 1990, a few months after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in August. The goal was to eventually go into Kuwait to repel the Iraqi military forces led by Saddam Hussein. But before that could happen, the Marines had to set up camp. Villescas stayed in the rear unit, building outhouses, setting up cots, and digging holes. By December, the Marines had moved to within 15 miles of the Kuwaiti border. Each day, Villescas and the other drivers transported fuel and water to the forward elements, switching shifts in a 24-hour rotation. By January 15, 1991, the 1st Force Support Group has managed to move up all the equipment and personnel needed for the planned U.S. airstrike in-theater.

Even before Operation Desert Storm officially commenced, Villescas realized that she was closer to war than she had ever anticipated she would be. One night, she awoke to the “percussion of rounds going off”—the earth-shaking sound of an aerial bombing. Scrambling to shepherd the 14 other women in her unit to the perimeter, she fled her tent wearing only her sweatpants. After that, she slept in her boots and cammies every night. When Operation Desert Storm began in earnest, bombing at night became commonplace. As Villescas put it, “Life as we knew it went out the door.”

Then, in February, the ground war known as Operation Desert Shield kicked off. Villescas’ commanding officer came to her and told her that she would be going into Kuwait.

But women weren’t allowed in combat, Villescas replied, confused. Had the rules changed? When had female Marines been authorized to go into Kuwait? They hadn’t been authorized, the commanding officer told her. There was simply no one else available to drive the resupply vehicles.

Villescas hesitated. She told the commanding officer that she wasn’t refusing to go in. But, she said, she needed to know that the actions that she and the other female drivers took in Kuwait would be documented. They were going to be doing something that women had not yet been asked to do—that women, in fact, were prohibited from doing.

The commanding officer, also a female Marine, told her she understood. She would make sure that there was a record of their actions. Indeed, “Operation Desert Storm witnessed the greatest participation ever of women Marines in a combat operation. Apart from a lack of privacy at times, the presence of female Marines was not an issue within the force itself.”

After Operation Desert Shield ended, Villescas spent three months in Saudi Arabia packing up and tearing down the tent city she had been living in. She was sent home to the U.S. for about four months in 1991. Then she was redeployed to Iwakuni, Japan for a year. She realized then that she had to leave the Marines. There hadn’t been enough time for her to process what had happened in Saudi Arabia. She was dealing with the shock of war. And she had to leave her family again, a separation which resulted in the end of her relationship. After her tour of duty ended in 1993, Villescas prepared to leave the Marines, which she did in 1994.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed id ultrices sem. Pellentesque gravida justo urna, ac blandit tellus feugiat sed. In aliquet, nunc id fermentum pellentesque, tortor metus egestas ante, finibus ullamcorper elit magna vitae odio. Praesent scelerisque sollicitudin efficitur. Duis bibendum accumsan tempor. Proin non semper nibh. Curabitur ac ligula imperdiet, auctor ex sit amet, viverra sem. Duis convallis est id magna fermentum pellentesque. Etiam nunc odio, aliquet at laoreet id, interdum nec purus.

The service summer uniform consisted of two-piece including a blouse and skirt made of green and white striped material, originally Plisse Crepe but later replaced by Seersucker. (A thin, puckered, all-cotton fabric, commonly striped and very common for summer clothing.)

The jacket had shoulders straps of same material, each fastened by a single button. Buttons for the jacket were white bone or composite.

Headwear for the summer service uniform was initially the Service “Bucket” cover, which was replaced in 1944 by the Summer Garrison Cap.

The handbag was the spruce green cover and shoulder strap.